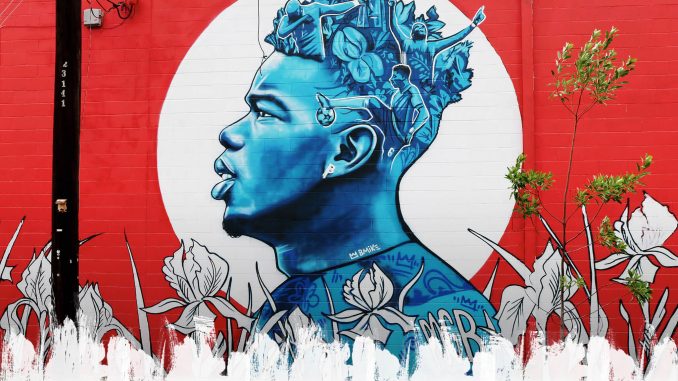

oung money, vanishing kicks and the death of the dab—a confrontation with the coolest athlete on the planet. Part 2 of Larger Than Life, a B/R Football celebration of World Cup superstars like you’ve never seen them before…this gigantic mural included 👆

BY AMOS BARSHAD ART BY BRANDAN “BMIKE” ODUMS JUNE 6, 2018

Okay! Paul Pogba shouts, smashing his hands together. “Let’s have some fun!” The genius midfielder who nearly has it all is marching through his cozy mansion here in the ritziest of Manchester’s suburbs, past his technicolor fish tank. Looks like there are some Siamese fighting fish in there. Maybe a couple of fantail guppies? He calls them Pogfish. Except for the sea star; that one’s called Rafstar. And when one of the exotic fish inside Paul Pogba’s aquarium is sick, the others poke at it, encouraging it back to good health. Also, sometimes, the fish eat each other!

A French video crew is on its way out the front door, and a sprawling photoshoot is prepping all over the damn place: The lighting rigs and the craft services and the stylists and the racks and racks of luxurious tracksuits combust into some sort of British movie-lot hideaway. At the foot of Pogba’s stairs, an almost life-sized faux-taxidermied lion keeps watch over us all, a match ball underneath one paw.

Out in the driveway, a young woman in house shoes picks her way carefully over electric cables, ferrying along a tiny Yorkshire terrier whom everyone greets with a delighted squeal. Rafaela, the do-everything agent, tends to the mess inside. At one point, with earned hyperbole, she shouts down someone requesting even more of Pogba’s time: “It’s a complete chaos here! A person who has to leave for two months needs time to make his bed, no?!”

Pogba himself remains pretty chill. One of the dozen or so anonymous crew members who is in his home, carrying around some piece of cumbersome equipment or another, unhelpfully points out to him that “there’s a lot of people in your house.”

“Yeah!” Pogba cracks. “Don’t you break anything!”

You have to be careful in P/P Arena—an actual indoor turf field, goals and all, smack in the middle of the house. The sides of the field are decorated with dramatic murals of Pogba mid-action; its ceiling is lined with zigzag laser beam bolts. Throughout the mansion, the branding rolls on: There’s a P/P gold-and-black foosball table and P/P embroidered pillows; on a counter in front of the flatscreen, an unopened box reads “P/P watch 1/1.” Tall black doors come with long crystalline handles.

My favorite bit of extravagance, though, is a side bathroom. It has an all-black toilet and a light fixture that, unlike the hanging orb-things or dangling silver stick-things found throughout the rest of the place, resembles—believe me—a perfect ’80s sci-fi alien cocoon. It looks like it should be dripping with otherworldly fluid and ready to hatch into the monster that murders us all. Instead, it automatically clicks on when you walk into the room.

Paul Pogba is 25 years old, and you might not think he’s as good as he looks—that he hasn’t broken free of everything he’s supposed to be, that he doesn’t deserve to celebrate quite yet. But the young man has dough, and he’s spending it exactly how he wants, and I am very, very happy for him. He’s wearing black denim shorts and a blue denim vest with vaguely Basquiat-style hearts and scribbles. On his feet are a pair of sock-sneakers—Adidas, of course. He’s one of their international poster boys. The laces dangle pointlessly loosely; they’re almost off the shoe altogether. I don’t quite know what to tell you: It looks extremely cool, and I immediately consider if I could go home, spend a little too much money and pull it off myself.

B/R partnered with street artist Brandan “Bmike” Odums and three world football superstars to paint their own self-portraits:

• THE ART: Paul Pogba Takes Over NOLA

• EARLIER: Mo Salah Makes The World Smile

• WATCH: Mo Salah Takes Over Times Square

• COMING SOON: Neymar Jr. Takes Over Miami

A few years back, Pogba made a public plea for a thief who had stolen a pair of his Louboutin sneakers to return them. As we sit down, that’s the first thing that comes to my mind: “Did you ever get the Louboutins back?” No, he reports, chagrined.

“Those shoes are stories. It was my first time to buy some expensive shoes, you know? So for like one week, I was thinking. I was feeling so bad because it’s like, ‘Wow, it’s so expensive. I cannot do this.’ Then I was like”—Pogba drops his voice into a focused whisper—”‘All right, let’s do it.’ So I bought two pairs at once, and I kept them because of the story! And they came to my house, and they robbed me. They took my Louboutins. They always know to take the best things.”

To this day, Pogba says, he still has some anxiety when splashing out. “I try to remind myself that, ‘Come on, you got it,'” he says. “But I check my bank account [before a big purchase]. I don’t wanna end up with no money. I try to do the right thing. Help the poor, help your family. That’s what God wants. That’s what makes me feel happy. You can’t worry too much about the clothes or the aquarium or whatever.”

He waves at his pescatarian pals. “It’s nice, to see the fishes and stuff like that. It’s cool. I really like it. But all this material stuff, at the end of the day, when you die, they stay.”

Pogba moved from Italy’s Juventus to Manchester United—the richest and most famous club in the world—in 2016. The transfer fee was €105 million. Neymar’s move from Barcelona to PSG a year later would quickly double the record. But at the time, that made Pogba, as the tabloids loved to scream, “the world’s most expensive footballer.”

The dramatic transfer made perfect sense. Pogba had history with United. And at Juventus, he was a dynamic operator in the midfield, possessed by the spirit. While Andrea Pirlo, il maestro, was tasked with controlling the flow of the game, Pogba was free to adventure. He’d blast out of the center of the pitch with 4D passes and virtuosic runs. And when the goalscoring chances came, he often as not finished with a blasting equanimity. In 2013, he won the Golden Boy award, given annually to the best under-21 player in Europe. A corresponding Tuttosport cover brandished his accomplishment. It sounded even better in Italian: He was the “Ragazzo d’Oro.”

Since the last World Cup, Pogba became known internationally for his celebrations—for capping off goals with powerful, joyful dabs, each of his long arms jutting out over his head in quick succession. In a quasi-autobiographical Adidas commercial, he was portrayed as a smirking, irrepressible force bursting through defenses and out of girls’ bedroom windows. He was lean and tall and beautiful. There was a grace to his devastation.

But the last two years in Manchester have slowed Pogba’s ascendancy. This past season, United finished second in the Premier League. Relative to its own ridiculous standards, that meant the club had underperformed. Worse, they were beaten to the league title, and handily so, by crosstown rivals Manchester City. Pogba’s own year had been defined not by dabs and grins but by a simmering cold war with his manager, the imperious Jose Mourinho, and a tetchy relationship with a stodgy commentator corps bizarrely obsessed with his intricate haircuts.

“When you’re a player who is signed for that money, when you dance like he does and when you’ve got hair like he has…” the former United right-back and Sky Sports broadcaster Gary Neville ranted at one point, toward no particularly salient point. At various times Mourinho would bench Pogba in favor of Scott McTominay, a humdrum prospect whose greatest asset was doing precisely what Mourinho told him to do. “A normal haircut, no tattoos, no big cars, no big watches, humble kid,” Mourinho grumbled in supposed praise of the Scot.

Pogba, who has a goddamn boat of a Rolls-Royce gleaming in his driveway, did his best to avoid the bait. Rightfully so. The chattering class was full of old men, and they were easily angered, and propriety is an easy cover for classism and racism. How exactly is an obscenely talented young man from France by way of West Africa who has money for the first time in his life supposed to act?

It’s all a reminder that Pogba has gotten so rich and famous so fast that fans and professional football watchers are still scrambling to understand him. What did we really know? By his own design, and with the manifold help of his corporate benefactors, he’d built himself into a blank icon—a pure paragon of ability and joy. So we were left, ridiculously enough, analyzing things like celebrations. What did the dab mean?

But this season, his relative silence, and his at-times maddening inconsistency, made him suddenly not that boundless fount of glee but something more…mercurial.

“Pogba is probably football’s closest equivalent to Kanye West,” columnist Jonathan Liew wrote in the Telegraph. “An unquestionable genius susceptible to squalls of mediocrity, a leader without a discernible cause, a mystery in plain sight.”

Stateside, Pogba is still being sold—alongside Beckham and Messi, in splashy Adidas ad campaigns—as an uncomplicated superstar. As a sure thing. But the organic glee that surrounded him in Italy has partly fizzled, partly curdled.

PEOPLE JUDGE ME MORE BECAUSE OF THE OUTSIDE FOOTBALL, WHICH HAS NOTHING TO DO WITH FOOTBALL—IT’S NOT LIKE IF I SPEND MORE TIME HAVING ONE HAIRCUT OR 10 HAIRCUTS, IT WILL MAKE ME PLAY BETTER OR PLAY WORSE.

—Paul Pogba

I ask Pogba about Gary Neville’s obsession with his hair, and he acts at first like he doesn’t even recognize the name. “I don’t really listen,” he says. “Football is not about the appearance of the player. It’s all about the pitch. I respect everyone’s opinion.” Then, laughing, Pogba breaks. “If he doesn’t like my hair, he doesn’t have to look at it. That’s it!”

What about Mourinho? What don’t people understand about your relationship with him?

“I would just say, because they’re not inside, they see what they see. They see us doing the talking, they straight away think it’s a problem. But if people think there’s a problem, what does that mean? It means maybe they want me to play. Mourinho, you know, he won with different clubs—he won so many titles. You cannot deny it. That’s his job. That’s what made him big like that. But the players, they’re the ones on the pitch. The coach tells you something and you do something else—you’re on the pitch. And then it hits you. You’re the one who has the last word.”

In pro sports in the U.S., coaches are generally less dominant than star players. Does that system appeal to you?

“In America, it is more freedom in their sport. It’s not about the look, not about this outside, but about what they do. You know? The American guy is, like, free. He can wear what he wants and they don’t judge him on this. And I really like that. It’s more freedom in their sport. Yeah, more freedom in their sport.”

Pogba was born and raised in Roissy-en-Brie, a banlieue 30 kilometers east of Paris. His brothers, Mathias and Florentin, are twins and older than Paul by three years; they were born in Guinea before his parents left West Africa. He grew up battling them from the age of three in a hilly, cramped field in the courtyard of their apartment complex. “I was always with them,” he says. “I was following them everywhere. And they were always stronger than me.”

I ask Pogba when, exactly, he realized he was better than his brothers. He politely demurs. “Oh, better, no … we don’t play the same positions. It’s always been tough to play against them, always!” Mathias and Florentin played professionally, most recently in semi-obscurity in the Netherlands and Turkey. Pogba’s equivocation is a remarkable stretching of the truth in the service of familial respect.

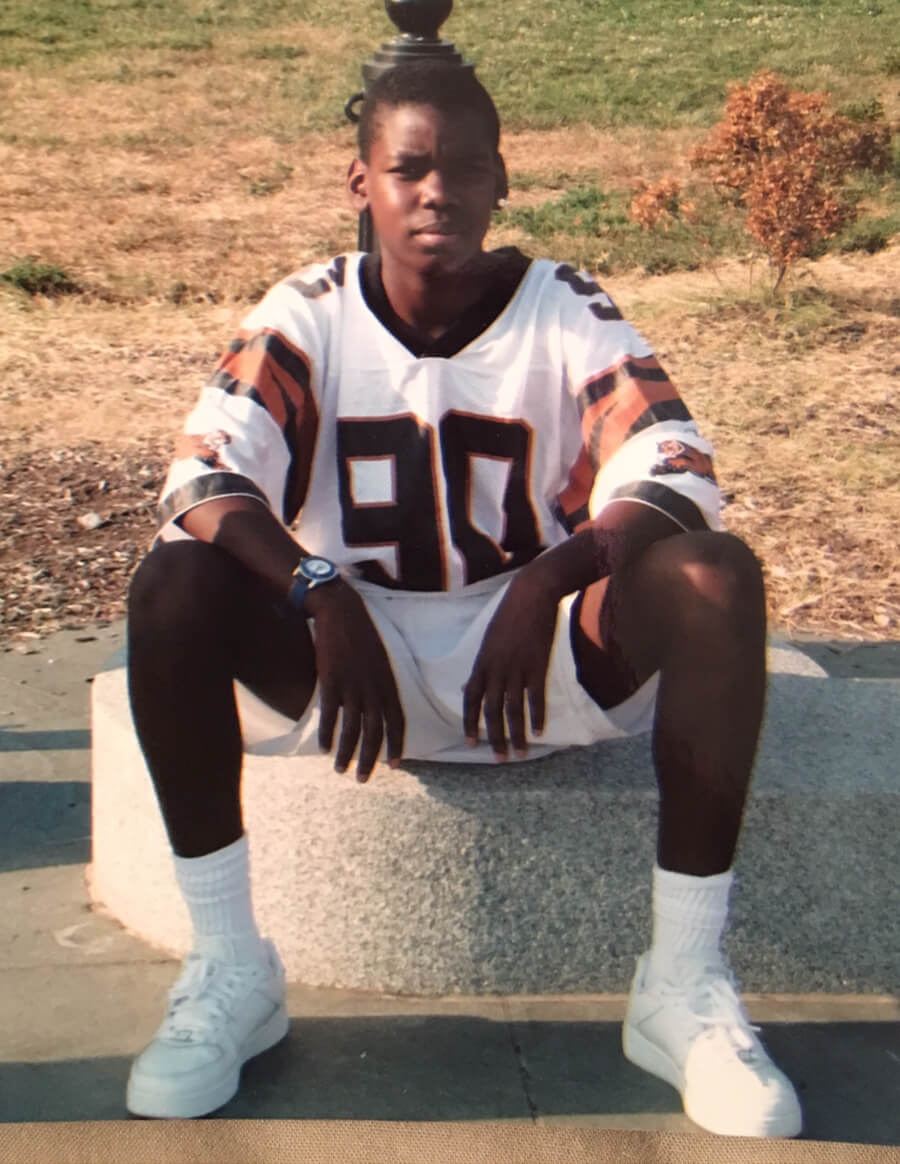

Photo courtesy Paul Pogba

Early on, he idolized Ronaldinho and his countrymate, Zinedine Zidane. He’d ceaselessly practice the latter’s “roulette” spin move and the former’s “flip flap.” “Those were the moves to do!” His earliest celebration was cribbed from Ronaldo. “Every time I scored I was like this,” he tells me, happily wagging an index finger in the air. And he’d score a lot. “When I was little, I didn’t want to give the ball. I was always keeping it. That was the thing [coaches] were telling me”—you have to learn to pass. “I wanted to win all the time. And I saw, I keep the ball and I score by myself? Then they can’t say nothing to me.”

Money wasn’t abundant in the childhood home, but Pogba never minded that much. A family trip as a teenager back to Guinea helped. “When you grow up in Europe and you go to Africa, you realize how lucky you are. It’s good for you, to see how things are in life.” (With the years, he’d only become more cosmopolitan: along with French and English, he now also speaks Spanish and Italian). By the time he was a teenager, he’d already left his local club, first to play for larger French clubs and then to move across the English channel to United’s youth academy. “I was like, 14, 15,” he recalls. “I was so happy to play for Manchester United. I couldn’t wait just to start training. Just to see the football. I was so proud of myself. My family was proud. It made me want to do more.”

To achieve more, he’d first have to leave England. It was at age 19 that he transferred to Juventus and began cashing in on all that potential. “When you’re at Juventus,” Pogba says, “you have to be a warrior. The way we train, the way we do preseason—it’s, like, to prepare for war!”

Then came the deal back to Manchester. With that infamous number: 105. Million. Euro.

The world’s most expensive footballer.

There’s a perception that, from the outside, the record fee changed everything. Is that how it felt from the inside?

“From the inside? No. For myself, no. But for everybody else, yes. It took me a long time to get used to this. Because they didn’t see me with the same eyes. It was, like, crazy. And I just had to get used to this.”

Did it ever make you think, “Oh, maybe we should have chopped a few million euro off that transfer fee…”?

“No, no, no! I knew, that’s how it is. Today it’s 100,000,000, tomorrow it’s 200,000,000, the day after it’ll be 300,000,000. A generation, then a generation, then a generation. Twenty years ago, how much was the most expensive player? Sixty million? Now 60,000,000 is normal.”

Was it a relief when Neymar eclipsed it?

“No, no relief. It’s never been a problem for me. I always want the same thing. To be the best. To work.”

In late March, in the midst of his rocky season with United, Pogba linked up with the French national team in St. Petersburg to play a friendly against Russia. From his social feeds, we saw Pogba at training sessions ahead of the match embracing Antoine Griezmann and Hugo Lloris, all of them in matching tracksuits; it looked, from the outside at least, like a great relief for him to be playing with his countrymates. A grinning Olivier Giroud even greeted Pogba and his latest hairstyle with a cheeky, loving, “How are you, my Pikachu?” In the match, early in the second half, Pogba lined up to take a free-kick. We hadn’t seen him do it in a while in a red jersey. But in the stark whites of France, he struck it wonderfully, lobbing it over the wall and slotting it bang into the left corner of the net.

As he sprinted across the pitch, he pulled up his France jersey—a flashy celebration, sure, but also something else. Underneath he revealed a T-shirt with a hand-scrawled message: “Joyeux Anniversaire Papa, Allah Y Hramou.” “Happy birthday, Papa. May Allah have mercy on him.”

Pogba’s father, Fassou Antoine, had passed away in 2017 at the age of 79 from an undisclosed illness. “It was a message to my dad, like, ‘I didn’t forget you,'” Pogba tells me. “‘You’re still in my heart.’ You know, it’s good for him, to look from upstairs.”

Of his father, Pogba says: “You know those people, they’re funny, but they’re just natural? He didn’t do it on purpose. The way he was talking, he was so funny. He always had some story to tell you about something. And it was hysterical. My brothers, my mom, we all laughed at my dad. He was special. Is special. There’s only one like him. He was so stubborn. And that makes him special. Like, when he has his idea, he was going to his idea. That’s a good thing, you know?”

In Pogba’s living room, I notice a framed photo illustration of Paul with his two brothers, all of them shirtless. The caption reads “Le Pogbance.” There’s also an illustration of a grinning, also-shirtless Pogba, this one sans brothers. In gold cursive there is the word “hamdulillah”—Arabic for “Thank Allah.”

Pogba is a devout Muslim. This time last year, on a pilgrimage to Mecca, he shared a video of himself with a man pulling off the world’s worst dab. Days after the end of this Premier League season, during Ramadan, he posted an Instagram video of himself in Mecca overlooking the Kaaba. He looked serene and in awe.

Mohamed Salah, the Liverpool striker who bows in silent prayer to celebrate each goal, has become a cult hero. But perhaps due to Pogba’s outside trappings—the jewels, the sneakers, loose and lost alike—Pogba’s faith hasn’t been acknowledged as seriously by fans.

For Pogba, there’s also the complicated reality of France’s relationship to Islam—the question of his country’s latent and not-so-latent Islamophobia. (Salah is Egyptian and so largely shares his faith with his countrymates.) Jonathan Liew, the columnist who compared Pogba to Kanye, has also pointed out that the beloved Zidane had once made a point of calling himself a “non-practicing Muslim.”

Do you ever feel any negativity directed to your faith? Either in the UK or in France?

“Well, no. Not that much. But I don’t even speak politics and stuff like that. Football can really…help those things. I don’t know if you know what I mean?”

Sure. Yeah. He wants to acknowledge to me that he knows his exalted position grants him a pass. He understands his position.

“Obviously, we cannot control the world,” Pogba continues. “We can control ourselves. And the thing that I’m trying to show everybody is respect. We’re all brothers in front of God. We came from the same man, Adam. When you’re religious, it’s like we’re all brothers. And at the end of the day, we’re gonna die all together. We’re gonna finish, under the ground, in the grave. And black, white, yellow, rich, poor—all have the same end.”

It’s the last Sunday of the Premier League season. Manchester. The €105 million man didn’t enter today’s match against Watford until late and, in his brief time, only got one real chance to do something. Trapping the ball in the air in an advanced position, he found himself with space ahead. Space to make an audacious cross-pitch pass. Space to gallop forward toward goal. A split second, there, to produce a moment of individual brilliance. Instead, Pogba brought the ball down and took one bad touch and turned a chance into nothing.

Soon enough, the club’s big names will be gone. Off, just like Pogba, to their national teams. But Manchester United won, and right now these people at this pub across the way from Old Trafford want to rip off their shirts and stomp and sing some more, OK? There are lots of smiles, and most look knocked slightly sideways, and there are kids here (of course), and it’s all a bit dodgy. In the middle is a bleary-eyed, bare-chested ginger man spinning his flannel shirt around his head like, yes, a helicopter.

“United!” goes the chant, “We love you!”

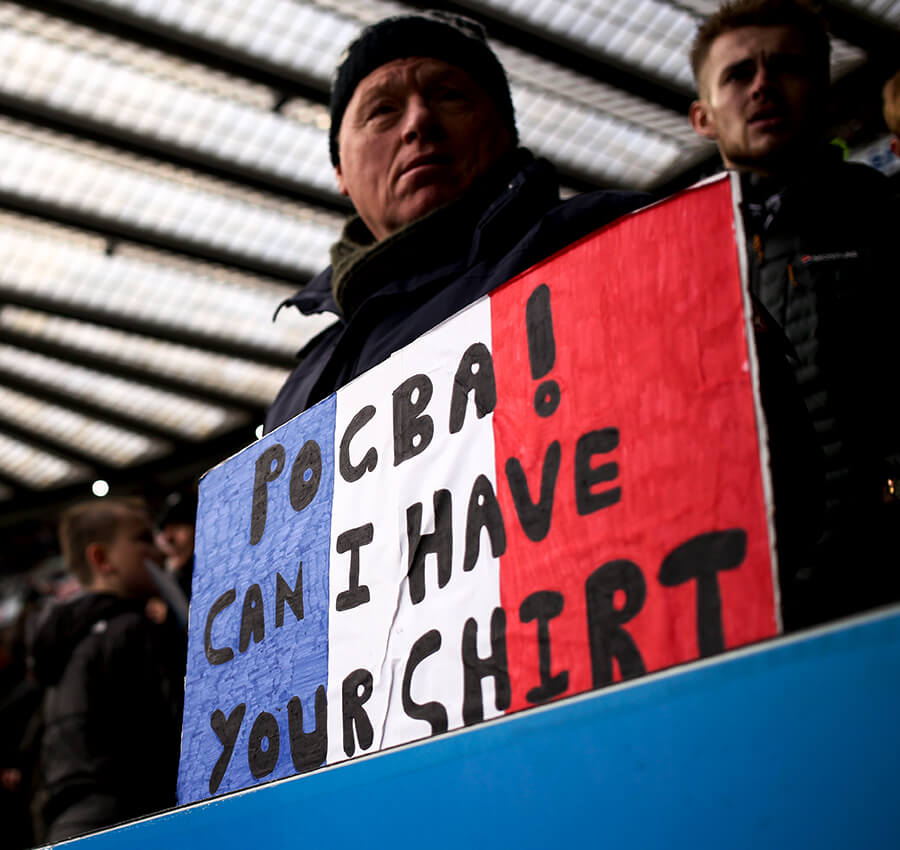

Getty Images/Robbie Jay Barratt

Out back behind the pub, there’s an abandoned office building with its windows smashed up all the way to the top floor. (Teens with BB guns? Teen with impressively precise rock-throwing skills?!) People walk in and immediately acquire massive beers and then immediately slosh-spill 10 percent off the top of their beers. An enigmatic quote from club legend Eric Cantona is plastered above us: “When the seagulls follow the trawler, it is because they think sardines will be thrown into the sea.”

Another chant flies by me. I just catch the part at the end that goes: “You’re a cunt! You’re a cunt!” And then everyone sings out a question, its answer a rhetorical mantra of positivity: “Who the fuck are Man Uniiiiiited! Who the fuck are Man Uniiiiited!”

The love of club is evident. It’s pouring out of the place. Less clear is support for Pogba, the most expensive man on the pitch. Outside, where vendors push “stuffing barms with apple sauce,” there are shirts for the former manager Alex Ferguson (“The Godfather”) and newish transfer Alexis Sanchez (“Welcome to Sanchezter!”), but you don’t see much Pogba merch at all. In nearby Liverpool, supporters sing songs to Mo Salah promising that if he keeps on scoring goals, they’ll convert to Islam. But in Manchester proper, even from the most blacked-out of the lads, you don’t hear songs for Paul Pogba.

The drive down to Pogba’s home from central Manchester takes you past a happy cliche’s worth of quaint brick homes and central greens. One sign meekly begs you to “please drive slowly through the village.” And in this particular foofy neighborhood, houses aren’t numbered but named. Things like “Hushed Meadow” and “Sleepy Pond” and “Slumbering Archipelago.”

But here in the mansion, instead of synonyms for riverlets, we get Pogba standing by his opulent fish tank. We get a glorious celebration of young money. A young man OK with where he is right now.

If he must eventually leave Manchester to rediscover that free-flowing beauty he had in Juventus, then he will. If Mourinho must go, then Mourinho will go instead. Right now, though, there’s a break from the intense churn of that interpersonal melodrama. Because right now it’s World Cup time.

“I’m telling you, I remember 1998, when France won,” Pogba says. He was five years old when Zidane led France, on home soil, to the glorious victory. “It was totally different in France. Everybody was happy. Everybody! France was happy! Everybody changed. I think everythingchanged! Even economically. Everything changed when they won the World Cup. So when we do this, I think, if we win”—then everything will change. For everyone. Again.

I ask him if he’s envisioned stepping out on the pitch for the first match against Australia in Kazan Arena and scoring the first goal for France. Pogba demurs again. He respectfully reminds me that he is a midfielder, after all, and that “my job, first, is not to score goals.”

“Of course, of course,” I say. But “if you do score—”

Smiling slightly, he stops me. “Win the first game. Win the final. That would be my dream. I don’t have any celebrations planned. I prefer to keep the celebration”—to keep it to himself. “I prefer to celebrate if we win the World Cup.”

Before we go, a cameraman for B/R puts forth what may have been, at some point or another, a reasonable enough request. Might the young man like to dab on film? Pogba winces. “You still on dabbing in 2018?!” He looks around the room, oozing incredulity. The dab had been good to him. But now, perhaps, it’s an albatross—a reminder of his earlier, freer, less complicated days. In a few weeks he’ll be in Russia: Show out, and he’ll shape a legacy and justify every hallowed word. Remind everyone that every last extravagance in his life is a trifle, a bauble, a distraction from the pure and good talent of Paul Pogba.

So why make the man dab? Can he live?

He looks around the room and makes eye contact with everyone and asks the question like he really, really wants an answer.

“Who dabs now?!”

Amos Barshad, a contributor to B/R Mag, has written for The FADER, Grantland, The New Yorker and The New York Times Magazine. He last wrote for Bleacher Report about David Blatt. Follow him on Twitter: @AmosBarshad

#LargerThanLife: Follow @BRfootball for more of the bigger stars, in their biggest moment, all World Cup long >>